Electrify Summary

I really enjoyed Electrify by Saul Griffith. It’s a very practical, rational, and optimistic book about how we can progress on the road to Net Zero. I’ve distilled my takeaways here, but would highly recommend reading the entire book to fully absorb the arguments and data provided.

Main Idea

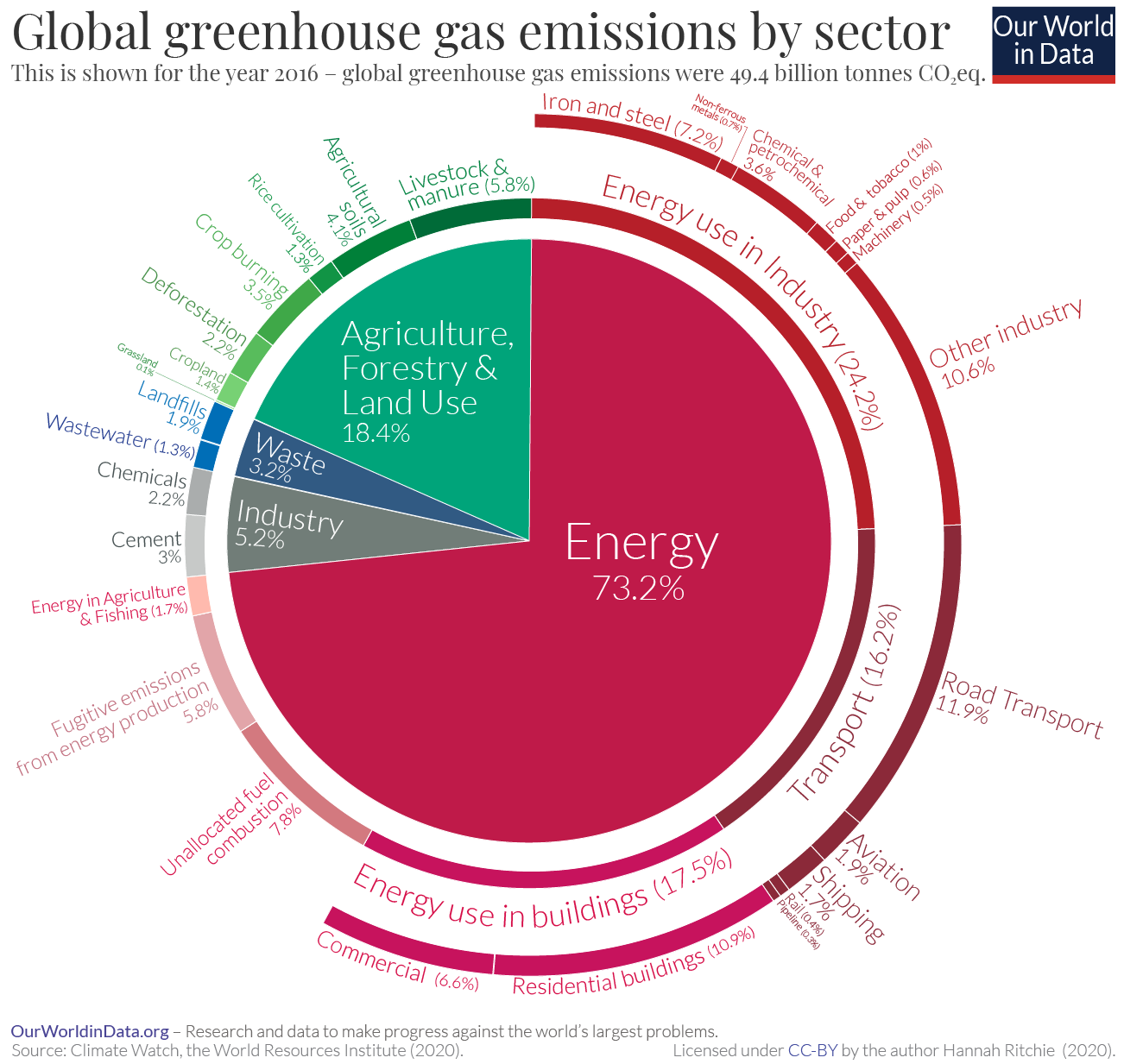

Nearly 75% of GHG emissions come directly from the energy sector. By electrifying the supply and demand of energy, we can make significant progress in driving this 75% down to zero. This is the most impactful and effective solution on the road to net zero because the technology is ready and scalable, though there are policy, economic, and cultural challenges to overcome. Other solutions are either complementary (i.e. they can help us eliminate the remaining 25% of GHG emissions after electrifying), or distracting false advertising from the incumbent fossil fuel players (e.g. hydrogen, “natural” gas), or miracles that we shouldn’t bet on (e.g. carbon sequestration).

Where does the 75% number come from? - “nearly 75% of greenhouse-gas emissions related to the US energy system” (8). This is illustrated in the following chart.

How do we electrify?

“America needs to decarbonize supply at the same rate as it decarbonizes demand, and that means powering electric machines with zero-carbon electricity.” (48)

- Electrify the supply - In the US, that electricity will come primarily from solar and wind. In some areas lacking solar and wind, other methods like hydroelectricity, wave and tidal power, offshore wind, and geothermal may contribute. Nuclear energy, a non-renewable resource, will play a moderate part in areas lacking other forms of electricity generation.

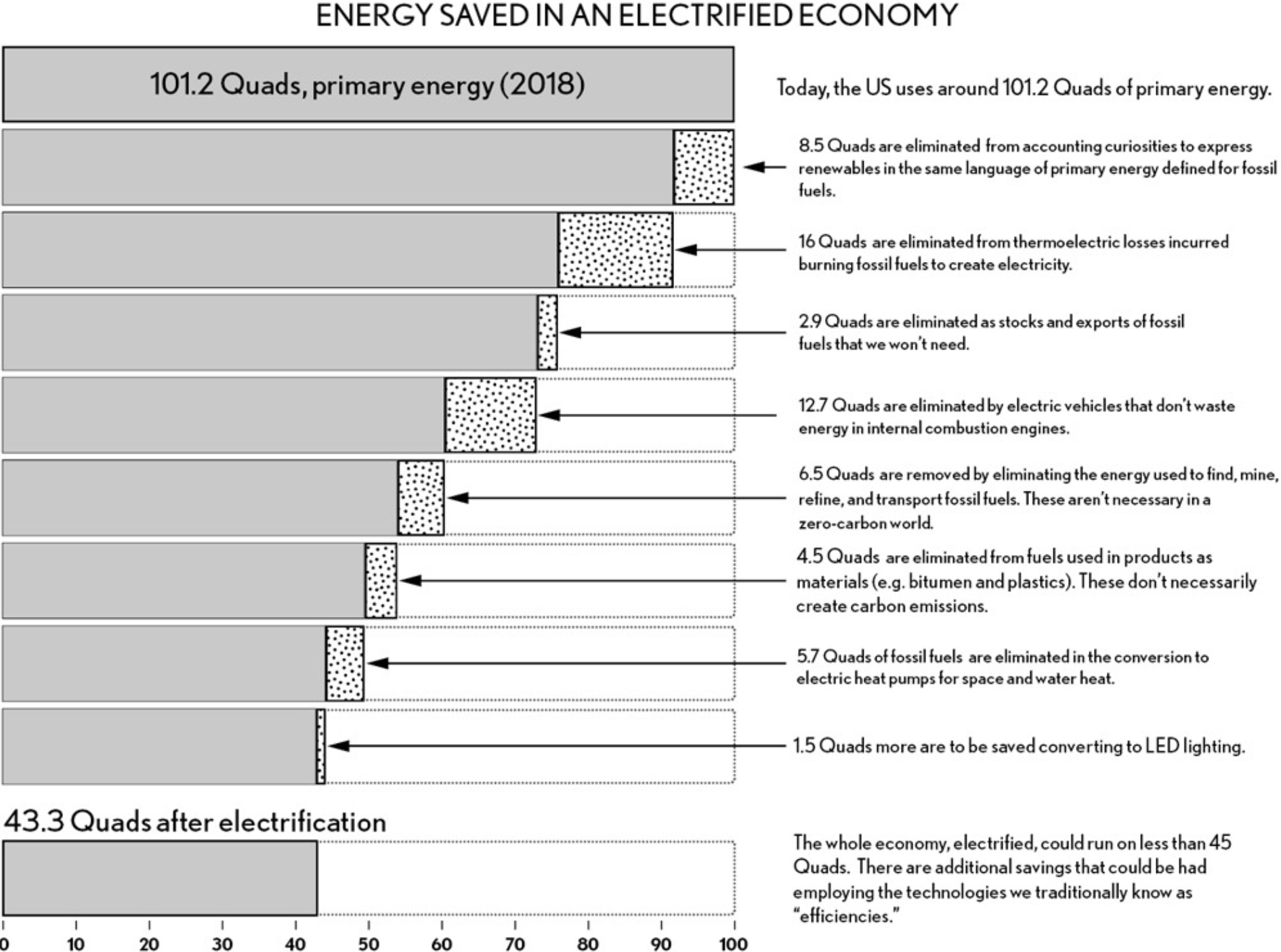

- Electrify the demand - Electrical machines are far more effective than their counterparts (e.g. internal combustion engines (ICEs)), so by electrifying the entire energy sector not only do we decarbonize the supply but we also reduce the demand for energy. As Griffith states, “Americans will only need half the energy they use today if we electrify everything while improving our lives.” (61)

What will it look like?

“In short, the climate-friendly future will be quite recognizable in terms of the major objects in our lives—our cars, homes, offices, furnaces, and refrigerators. All of these objects will just be electric. There is no need to fear this future, and there will be cost savings and health benefits if we embrace it—oh, and this will also address climate change at the same time.” (61)

The Role of the Individual

What can individuals do? Don’t focus too much on “the daily grind of small decisions”, your “personal climate footprint is largely determined by a handful of infrequent decisions” (5). You just need to make a few big decisions well (98). Those decisions are:

- Personal transportation - when the time comes to buy a new car, buy an EV. Otherwise, reduce transit-related fossil fuel usage as much as reasonably possible (e.g. public transit, carpool).

- Personal electrical infrastructure - install solar in your home at the next opportunity.

- Personal HVAC infrastructure - replace furnaces with electric heat pumps, insulate and seal homes, choose efficient single room heating and cooling systems.

- Home appliances - choose the most efficient electric options.

- Personal energy storage - get a home battery.

- Community infrastructure- support clean, renewable energy installation in your community.

- Diet - eat less meat, especially less beef.

“Let’s release ourselves from purchasing paralysis and constant guilt at every small decision we make so that we can make the big decisions well” (49).

See Appendix B for more specific recommendations by occupation.

The Details of Electrification

How exactly does electrifying everything reduce demand for energy?

Where will we get all the land for solar and wind generation?

Land use is an important factor. Solar and wind installations will require lots of land area. We can install solar panels on existing rooftops, parking structures, and along roads. We can install wind turbines on crop land.

How do we ensure supply 24/7/365?

There is an inherint reliability challenge to using clean renewable energy: renewable energy is intermittent. Solar energy is generated by day, wind energy by night, but we’ll need energy when the sun is down and the wind isn’t blowing. Additionally, the grid must always be balanced, i.e. consumption must always match production, which is a problem when the wind blows exceptionally hard or we have a lot of solar energy generation online. We can address these challenges with several solutions:

- Energy storage by all means possible.

- Batteries are great for short-term storage, but they have real problems: they only last around 1000 cycles and they can’t store energy long-term (e.g. store solar energy from the summer to use in the winter). We need the combined cost of solar and batteries to beat the cost of the current grid-based electricity at 13 cents/kWh.

- Use the batteries in EVs to store some energy for homes.

- Smarter storage and consumption profiles in existing systems: refridgerators, HVAC, in-house thermal storage systems.

- Utility-scale pumped-storage hydro

- Demand response - Shift energy use to periods of high solar/wind activity if possible.

- Residences can network devices in communities to draw their load at the right time and not all at the same time (like Nest thermostats do already): shift pool pumps, hot water heaters, refridgerators, thermal loads, dishwashers, clothes washers to run when renewable energy supply is high

- Industrial and commercial sectors can shift loads to line up with supply curves. These shiftable loads include:

- The load in the cold chain that keeps food cold (easy to shift)

- Manufacturing loads can overproduce during periods of high energy supply. Just as we overproduce grain and store surplus for the winter, we can overproduce nonperishable products. It is cheaper to store the products than the energy needed to produce them when the energy supply is low.

- Transportation - EVs can be charged when the renewable energy supply is high, e.g. at night when the wind is blowing or during the day when the sun is shining. Large night time loads are rare because most people are sleeping, but EVs can provide that demand.

- Load management - our residential loads currently do not match the generation curves of solar and wind, but the more we electrify, the easier it is to smooth out the demand curve (e.g. charging EVs at night).

- Diversification and long-distance transmission - We need to build a diverse portfolio of energy generation across the US to ensure instantaneous nationwide demand is met. Due to natural fluctuations in weather patterns, some regions will be generating energy while others are not. For example, the Southwest may generate excess electricity from solar energy during the day, while the central U.S. generates excess electricity from wind energy at night. If the long distance transmission infrastructure is extended to send electricity across state lines, then all regions will have their demand met with nationwide supply.

- Abundance - Solar and wind energy generation is cheap compared to storage. Over-build so that the minimum production at any given season meets the demand, e.g. January is usually the month with the lowest supply, so make sure the system can supply enough electricity in January. This would result in overbuilding by only 20% and is much cheaper than investing in energy storage tech.

- Grid neutrality - Everyone on the grid must be treated as an equal producer and consumer, which is currently not the case in the U.S. “Right now, if you have solar panels, you may sell some of your energy back to the grid, but often with caveats, such as the requirement that you can only sell back as much as you use so the accounts balance to zero at the end of the month. We need to make it universally possible for households to connect as much solar and storage as they like… We need a grid that treats everyone connected to it as both a supply and a demand, a load shifter and a battery. Let’s start demanding grid neutrality. Join the board of your rural co-op. Write your representatives. Get elected to a state utility commission.” (95) Imagine a grid that was as open-source as the internet, where everyone can freely contribute, consume, and create value.

How will we finance this?

Financing is key! Just like the financing innovations of the 20th century (e.g. mortgages, infrastructure financing), we need climate loans, i.e. low interest rate financing for the new climate infrastructure available to individuals and businesses, because both will play a huge part. If the financing isn’t there, it’s going to prevent a lot of people from participating in the transformation.

- Renewable energy is cheaper than fossil fuel energy over time, but requires higher upfront capital costs both for residential and commercial infrastructure. “Most families currently can’t afford the up-front costs of decarbonizing their households that will save them money in the long term. If US policymakers can offer ‘climate loans’ at the right rate, the transition to clean energy will start saving us money today. We’ve created these types of loans before, notably long-term mortgages to enable home ownership after the Great Depression” (125). Government-backed, low-interest climate loans, similar to government-backed home loans, would make the infrastructure revolution much more financially accessible to the average American.

- “Climate change doesn’t care about your household budget or economic circumstances, and unfortunately this means there is currently a disparity between rich and poor in incentives and access to clean energy” (125).

- “Whether we can transition to this cheaper future will largely depend on how we finance it. Basically, it comes down to an interest rate. We need to figure out how to help families buy now and pay later” (126).

- “Clearly, developing financing methods and institutions for this type of infrastructure, including bond measures, public-private financing, and regulated utilities, can significantly aid adoption. Policymakers and manufacturers need to offer solutions with finance, product, and policy, at every one of Americans’ purchasing decisions. We also need financing that works for landlords, and for shared infrastructure for people who don’t want to own a car or a house. If done right, innovative, low-cost financing will be the most effective way to ensure equity and universal access to cheap, reliable energy in the twenty-first century.” (128-129)

What about all those fossil fuel assets?

- “A 2018 study in Nature Climate Change estimated that as much as $4 trillion would be wiped from the global economy by stranding fossil fuel assets. By comparison, a loss of only $250 billion triggered the crash of 2008—remember ‘toxic assets’? Stranding fossil assets would affect not only energy stocks, but also investments in other industries and equipment related to fossil fuel, from gas stations to pipelines to oil tankers. Like the 2008 crash, the rippling effects of such an event could be catastrophic. Clearly, we can’t just pull the rug out from underneath the industry that gave us modernity. We need a plan.” (133)

- Instead of fighting them, why not buy out fossil fuel companies’ assets for the profit, $6-9 trillion, and invite them to build the clean energy future? The only thing holding them back are their assets, but otherwise they are masters of infrastructure, building, and financing capital-intensive projects. That’s exactly what we need.

What policies and regulations do we need?

- We need to update policies, regulations, permitting processes, and building codes that currently make it 3X as expensive to install rooftop solar in the US (compared to Australia).

- Grid neutrality should be implemented. Utility companies don’t like this idea because that dissolves their energy generation monopoly, limiting them to facilitate distribution which isn’t nearly as profitable.

R&D and other Opportunities

What is the role of Research & Development (R&D)?

“Aggressive research and development is necessary to achieve the fastest possible pathway [to decarbonization], but not in the way most people imagine.” We need to focus on the solutions that are ready to scale, not bet on solutions that are not yet ready. “There is a role for R&D in reducing the cost of the things we need for immediate deployment, but the heavy lift for R&D is in the cleanup projects - finding new ways to decarbonize the sectors that we know we don’t have an answer for. Most of these challenges are in either agriculture or materials, and they deserve out attention and resources if they are to provide solutions in the 10-20 year timeframe we need them to” (169). Some of those areas are:

- Reduce consumption -

- “In addition to using our material economy to sequester carbon, we need to start thinking big about how to use fewer materials to achieve the same goals, how to achieve 100% recycling rates of those materials, and how to use materials that have lower toxicity.” (175)

- “One way to reduce the need for electricity is if we simply buy and throw away a lot less stuff. The great majority of all of the materials we use eventually wind up in a landfill, and landfills themselves are a significant source of emissions as the buried cellulose decomposes anaerobically into methane” (178)

- Make things last longer. “The energy used to make an object is amortized over its lifetime. This is why single-use plastics are a terrible idea. It is also why the easiest way to make something “greener” is to make it last longer. I’ve always loved the idea that we could turn our consumer culture into an heirloom culture. In an heirloom culture, we would help people buy better things that would last longer, and consequently use less material and energy. There is an old adage that rich people can’t afford to buy cheap things of low quality—a statement of the fact that well-made things last longer. This is the environmental embodiment of that parable. Buy good-quality things and use them for a long time. This once again gets to the financing issue, however. Often the right choice is more expensive up front. Again, US policymakers will need to think about how to help consumers finance the right material and product choices.” (179)

- Cement - “Cement is another big energy consumer and CO2 producer, but we don’t yet have a scalable alternative. This represents a giant opportunity: Roman and Greek cement absorbed CO2, and this might be a case of back to the future by using cement to sink carbon. Cement is also what we need to make humanity’s favorite material, concrete…It is estimated that 8% of global emissions come from cement alone. Half of those emissions are from the energy required during production, and the other half are emitted in the creation of clinker, the lime-based binder that holds it all together. Limestone (CaCO3) is heated to become lime—calcium oxide (CaO)—which creates leftover CO2. But it doesn’t have to be this way. We should be able to make cement that absorbs CO2 through its lifetime. And we certainly should be able to build with less concrete. Covering ground with concrete has negative effects on drainage, soils, and more. I’m sure we can do better.”

- Plastics - Plastics are a huge problem. Their production generates “nitrous oxides and other gases even more harmful to our atmosphere than CO2”. Additionally, they don’t ever biodegrade; instead, they break down into harmful microplastics that enter the water basin and oceans. These microplastics cause serious digestive harm to the marine life, and will eventually cause harm up the food chain all the way to humans (digestive, cancer). “Less than 10% of plastic is recycled in the US. So recycling doesn’t work,…” “we need a combination of consumer behavior change and new technology to solve this problem.” “we should also invest heavily in synthetic biology or other pathways to a new kind of polymer that would quickly biodegrade the way leaves do. “

- Materials processing - Reduce the energy required for high-temperature / high-energy operations like grinding of materials, electrochemical processing, food processing, bending steel, melting aluminum, baking ceramics.

- Solar array and battery recycling - we need so much of it for the future that we need to figure out how to recycle 100% of solar arrays and batteries.

- Additionally, we need to resolve the ethical issues around batteries,… “Emmanuel de Merode, a Belgian prince, has devoted his life to protecting Virunga National Park in the DRC, including its highly endangered population of mountain gorillas. Emmanuel was shot multiple times and… lived to tell the tale, while trying to prevent the encroachment into these precious habitats of the very mining companies that give us our cobalt.” As the book ends, “We might be compelled to fix climate change to save humanity, or to save the creatures, or both, but it won’t be much of a victory if we lose the apes and the dolphins and the polar bears along the way.” (187)

- Electrify doesn’t go into this, but the Cobalt mining conditions in Africa, more specifically the DRC, are very dangerous, and lithium mining and extraction is notorious for its environmental hazards.

- Alternative materials - that are “less-exotic and less-toxic”, replacing cobalt, lithium, neodymium, cement, etc.

Other Important Considerations

Climate change and GHG emissions aren’t the only problem humanity faces today. There are other problems like the proliferation of microplastics in the water supply. Additionally, climate change often runs up against conservation efforts in its land grab (e.g. utility-scale solar/wind array installations) and encroachment on animal habitats (e.g. cobalt mining threatening gorilla habitats in the Democratics Republic of Congo). We can’t ignore these other pressing issues or sacrifice other species in our quest to address the climate challenge.

Yes, and…

In this section, Griffith answers common questions and rebuttals.

What about carbon sequestration?

- Most of these ideas are promoted by the fossil fuel industry to continue business-as-usual, including capturing CO2 from thin air, from smoke stacks, and from cars, furnaces, or kitchen stoves (191-193).

- “All of the planet’s trees and grasses and other biological machines pull a grand total of about 2 GT of carbon a year. To put that in context, our fossil burning is emitting 40 GT a year. Imagining that we can build machines that work 20 times better than all of biology is a fantasy created by the fossil-fuel industry so they can keep on burning.” (191)

- “The worst version of carbon sequestration is the most seductive one: capturing CO2 from thin air. This is energetically difficult… you have to sort through a million molecules to find the 400 that are carbon, then convince those 400 to become something they don’t naturally want to be: a liquid or, better yet, a solid. That sorting and conversion costs energy––a lot of it. Even if we could make it work reasonably, we’d have to install zero-carbon energy to run it, which is like using zero-carbon energy to supply our energy needs anyway, except it’s more complicated and expensive to add the carbon-sequestration step.” (192)

- “Renewables are already competitive with coal and natural gas in most energy markets”, so even if fossil fuel consumption was paired with carbon sequestration, “the added expense of carbon sequestration is not going to help fossil fuels compete.” (193)

What about natural gas?

- It’s not clean. It’s “largely methane, mixed with ethane, propane, butanes, and pentanes. When natural gas burns, like other fossil fuels, it emits carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and other carbon, nitrogen, and sulfurous compounds into the atmosphere, contributing to the global greenhouse-gas effect and local air pollution.” (194)

- It’s also promoted as a bridge fuel by those who stand to profit from the confusion (194)

What about fracking?

- It’s a distraction from solutions that will actually work.

- “Fracking spews methane directly from the mining sites, which offsets the nominal win from burning natural gas instead of coal. It also leaks from its network of distribution pipes. There are many other underlying problems with mining natural gas, such as water-table pollution and the creation of seismic instabilities.” (194)

What about hydrogen? (196)

- “The majority of hydrogen sold today is actually a byproduct of the natural-gas industry. Only a tiny amount of gaseous hydrogen exists naturally on earth.” (196)

- “As a battery, hydrogen is pretty ordinary; for the one unit of electricity you put in at the beginning, you probably get less than 50% out at the other side. This is called “round-trip efficiency.” To run the world off hydrogen, we’d have to produce twice the amount of electricity that we currently produce, which would itself be a monumental challenge. Remember, chemical batteries typically have 95% or so round-trip efficiency.” (196)

What about a carbon tax?

- “A carbon tax isn’t a solution. A carbon tax is a market fix meant to make all of the other solutions more competitive.” (196)

- “Carbon taxes might have been sufficient if we’d started with them in the 1990s, but for the taxes to achieve the 100% adoption rates we need now, they would have to ramp up very quickly. They would also be difficult to implement, as well as regressive, hitting lower-income people hardest.” (196)

- “It would probably be just as effective to eliminate fossil-fuel subsidies, which in many markets would tip the scales in favor of alternatives anyway.” (197)

- “A carbon tax is useful in decarbonizing the hard-to-reach end points of the material and industrial economy” (197)

What about technological miracles?

- Don’t bet on a miracle.

What about the existing utilities?

- “There is no way we win this war without the utilities. We need them to deliver three to four times the amount of electricity they do today. They are perfectly poised to be a giant participant in our clean-energy future. Utilities should be the natural leaders in this project, as they already have five valuable characteristics…: 100% market penetration, 100% billing efficacy, 100% knowledge of how we use electricity today (if they want to know it), access to low-cost capital, and an incredible local workforce in every zip code.”

What about meat?

- “Eating less meat remains one of the easiest consumer decisions to reduce climate impact, but it alone cannot solve our climate problem…Meat-eating doesn’t have to go away completely, but Americans do need to become more conscious about their diets.” (198-199)

What about the rest of the world?

- “If America leads, however, it is likely that other countries will follow once they see the economic advantages of doing so. The early movers will own the lion’s share of these critical twenty-first-century industries.” (200)

Can we make enough batteries?

- We will need a lot of batteries, but that’s why we need the WWII-like mobilization, to build the energy goods of tomorrow